How did we get here?

TRL is 88 years old. Since its creation in 1933, the company has made many positive contributions to road transport and other areas of science and technology. Examples include invention and development of the mini roundabout, development of the Hazard Perception test and the zebra crossing, fundamental work to improve vehicle standards, and even helping in the second world war effort. One of the most historically-valuable items in the TRL archive is the original visitor’s book from the 1930s and 40s. An entry from 1941 stands out – the original hand-written signature of an engineer and scientist named Barnes Wallis, who by all accounts was visiting to discuss a novel idea he was working on at the time. TRL is full of history.

The Smart Mobility Living Lab (SMLL) is 1 year old and might be considered as another one of TRL’s positive contributions to transport innovation. It is an evolution of TRL in many ways, but perhaps the most important is the ‘extra L’ in its name. The ‘Living’ is what makes the work in the SMLL special; moving from the track and simulation work for which TRL is famous, to testing new technologies in the real ‘living’ world. If we are to achieve a smart mobility system in the future, which is what we need to do if we are to make transport carbon-neutral, safe, and accessible, then we need smart testing.

The Smart Mobility Living Lab (SMLL) is 1 year old and might be considered as another one of TRL’s positive contributions to transport innovation. It is an evolution of TRL in many ways, but perhaps the most important is the ‘extra L’ in its name. The ‘Living’ is what makes the work in the SMLL special; moving from the track and simulation work for which TRL is famous, to testing new technologies in the real ‘living’ world. If we are to achieve a smart mobility system in the future, which is what we need to do if we are to make transport carbon-neutral, safe, and accessible, then we need smart testing.

On the 30th of September 2021, the SMLL celebrated its first birthday with an event hosted at its offices in Greenwich, with members of its innovation community (a community which is 1 year old) in attendance. Lots of us from TRL attended, and in the weeks leading up to the event we were grappling with varying travel plans, complicated by the current fuel supply crisis and ongoing concerns over Covid.

How did we get there?

The day before the event myself, Richard Cuerden (TRL’s Academy Director), Neale Kinnear (Head of Transport Safety), and George Beard (Head of New Mobility) realised we would all be taking a familiar journey into Waterloo on the train as the first leg of our journey. Our plans from that point however, differed. Richard had decided to keep it simple with an onward train from Waterloo East. George was staying true to his strategy area and hiring an e-scooter. Neale would be taking the boat from the London Eye. I had decided to cycle door-to-door on a Brompton folding bicycle.

The focus of the SMLL’s work can be thought of as (to quote Michael Hurwitz of Arrival, who presented at the event) “…elevating the experience of moving around”. It seems appropriate therefore to report on what our respective experiences were of ‘moving around’ between Waterloo and Greenwich, as we approached the event.

... by bicycle

My own journey was an absolute breeze. It was relatively long – 1 hour and 25 minutes including faffing with folding and unfolding the bike and finding my way on Strava – but it never felt like a chore. My route was ‘side roads and Thames Path where possible’. I can honestly say the only downside was the cobbles. Sure – there were poorly maintained pavement surfaces all over the place, and even a crane or two to avoid near all the building sites, but all this never felt annoying; clearly investment is needed, and it will surely come as the transport system moves towards active- and micro-mobility being the default for shorter journeys (which it needs to). Most importantly, I enjoyed the travelling as I was doing it. This is rarely something I say. For someone who works in mobility, I really don’t enjoy most of my experiences with transport (trains, buses, planes, cars, and boats alike – they almost all make me travel-sick and fatigued). Cycling though felt awesome, and if I ever find myself needing to travel much more than I do now in the ‘new normal’ of hybrid working, it will be to the bike that I look wherever possible. I’ll just have to put up with the cobbles.

My own journey was an absolute breeze. It was relatively long – 1 hour and 25 minutes including faffing with folding and unfolding the bike and finding my way on Strava – but it never felt like a chore. My route was ‘side roads and Thames Path where possible’. I can honestly say the only downside was the cobbles. Sure – there were poorly maintained pavement surfaces all over the place, and even a crane or two to avoid near all the building sites, but all this never felt annoying; clearly investment is needed, and it will surely come as the transport system moves towards active- and micro-mobility being the default for shorter journeys (which it needs to). Most importantly, I enjoyed the travelling as I was doing it. This is rarely something I say. For someone who works in mobility, I really don’t enjoy most of my experiences with transport (trains, buses, planes, cars, and boats alike – they almost all make me travel-sick and fatigued). Cycling though felt awesome, and if I ever find myself needing to travel much more than I do now in the ‘new normal’ of hybrid working, it will be to the bike that I look wherever possible. I’ll just have to put up with the cobbles.

... by water

Neale’s journey began with a short walk to the London Eye to catch the boat to Royal Arsenal. Coincidentally, his journey also took around 1 hour and 25 minutes. Several things about the preparations were less ‘smart’ than we might like. For example, Google Maps did not suggest the boat as an automatic option. Ticketing was confusing, as Neale was told at his origin station that an ‘all-zones’ Travelcard would cover the trip, but this turned out to be wrong. Instead, what happens is the Travelcard provides a discount for the boat ticket, which meant that since Neale did not need his Travelcard for anything else, it would have been cheaper for him to buy separate tickets for each leg of the journey. When he arrived at the pier near the London Eye, there was more confusion. There were no staff, and it was not clear which boat he was even supposed to catch. Thames Clipper? Uber Boat? Water Taxi? Multiple terms like these, and unhelpful timetable codes like ‘RB1’ provided little clarity. Luckily, when Neale got on the boat, things improved. He said it was ‘surprisingly pleasant’, with comfortable seats, a café which had app integration and in-seat service, and at most seven other passengers. This last point might be a red flag for sustainability, but presumably reflects a lack of awareness in the commuter population (or confusion, need, or price), and that the boat itself might be perceived as being better suited to tourists than commuters. Neale did observe that his journey was pleasant and relaxing, and that it prompted him to appreciate some of the architecture on his journey in a way he may not have on another mode.

Neale’s journey began with a short walk to the London Eye to catch the boat to Royal Arsenal. Coincidentally, his journey also took around 1 hour and 25 minutes. Several things about the preparations were less ‘smart’ than we might like. For example, Google Maps did not suggest the boat as an automatic option. Ticketing was confusing, as Neale was told at his origin station that an ‘all-zones’ Travelcard would cover the trip, but this turned out to be wrong. Instead, what happens is the Travelcard provides a discount for the boat ticket, which meant that since Neale did not need his Travelcard for anything else, it would have been cheaper for him to buy separate tickets for each leg of the journey. When he arrived at the pier near the London Eye, there was more confusion. There were no staff, and it was not clear which boat he was even supposed to catch. Thames Clipper? Uber Boat? Water Taxi? Multiple terms like these, and unhelpful timetable codes like ‘RB1’ provided little clarity. Luckily, when Neale got on the boat, things improved. He said it was ‘surprisingly pleasant’, with comfortable seats, a café which had app integration and in-seat service, and at most seven other passengers. This last point might be a red flag for sustainability, but presumably reflects a lack of awareness in the commuter population (or confusion, need, or price), and that the boat itself might be perceived as being better suited to tourists than commuters. Neale did observe that his journey was pleasant and relaxing, and that it prompted him to appreciate some of the architecture on his journey in a way he may not have on another mode.

... by e-scooter

George’s journey was the third to come in at around 1 hour 25 minutes. Honestly, we did not plan this. Using an eScooter in one of the current London trials, the booking and unlocking of the scooter was very easy and intuitive using the app. The ride was pleasant on the quiet roads and the cycle superhighways, although there was some robust vibration on rough patches. Another observation was that the 12.5mph limit felt quite slow, with cyclists overtaking the scooter at will; the geofencing also sometimes restricted the scooter to 5mph as it (erroneously) assumed a straying onto the footpath – this is obviously something that will need fixing as we move to a system with more micro-mobility solutions to manage space. Although George has been researching electric vehicles for nearly a decade now, and he knows that their capabilities are often underestimated by users, he was surprised to find himself experiencing range anxiety as he watched his scooter’s charge diminish as he travelled. It turned out though that this anxiety was well-founded, as his scooter ran out of charge before he had reached his planned destination (Blackwall) and he had to abandon it at Limehouse and continue his journey on the DLR from there (the DLR was pleasurable from start to finish).

George’s journey was the third to come in at around 1 hour 25 minutes. Honestly, we did not plan this. Using an eScooter in one of the current London trials, the booking and unlocking of the scooter was very easy and intuitive using the app. The ride was pleasant on the quiet roads and the cycle superhighways, although there was some robust vibration on rough patches. Another observation was that the 12.5mph limit felt quite slow, with cyclists overtaking the scooter at will; the geofencing also sometimes restricted the scooter to 5mph as it (erroneously) assumed a straying onto the footpath – this is obviously something that will need fixing as we move to a system with more micro-mobility solutions to manage space. Although George has been researching electric vehicles for nearly a decade now, and he knows that their capabilities are often underestimated by users, he was surprised to find himself experiencing range anxiety as he watched his scooter’s charge diminish as he travelled. It turned out though that this anxiety was well-founded, as his scooter ran out of charge before he had reached his planned destination (Blackwall) and he had to abandon it at Limehouse and continue his journey on the DLR from there (the DLR was pleasurable from start to finish).

... by train

Richard’s journey was a simple walk through to the Waterloo East station, a train to Woolwich Arsenal, followed by a 3-minute walk at the end. His journey was by far the quickest of us all – taking just 45 minutes including the transfer. In all his discussion about it on our joint chat group the main topic of conversation was mask-wearing, which was near 100% for most of the journey (compared with around 25% on the train into Waterloo). He sent us a smug photo from the SMLL on arrival too, noting that he was just heading next door to a café for breakfast. Richard is our boss, and as such I can tell you that we were all delighted that he made it nice and early; we were in no way unhappy that he was in a café while we rode, floated, scooted (and replanned) our journeys to join him at the birthday bash.

Richard’s journey was a simple walk through to the Waterloo East station, a train to Woolwich Arsenal, followed by a 3-minute walk at the end. His journey was by far the quickest of us all – taking just 45 minutes including the transfer. In all his discussion about it on our joint chat group the main topic of conversation was mask-wearing, which was near 100% for most of the journey (compared with around 25% on the train into Waterloo). He sent us a smug photo from the SMLL on arrival too, noting that he was just heading next door to a café for breakfast. Richard is our boss, and as such I can tell you that we were all delighted that he made it nice and early; we were in no way unhappy that he was in a café while we rode, floated, scooted (and replanned) our journeys to join him at the birthday bash.

Mobility as an experience

What does this all tell us? My summary would be this. First – cycling is amazing for the mind, body, and soul. It is easy, accessible, clean, healthy, and relatively quick. Second – there are loads of ways of getting around in London, but every time there is any kind of interface between modes, or between a mode and an app, things can (and do) go wrong. There is still a lot more work to be done – the public transport user experience is far from seamless as illustrated above. There are lots of pain points, and aside from environmental motivations, just about the only reason for not making the journey to SMLL by car was traffic congestion. This is not good enough for shifting the mass market away from private car use. Lastly – ‘mobility’ is a verb in which people have experiences. ‘Smart mobility’ should be too. Which takes us on to the event at SMLL.

We’re at a birthday party. Where are we going next?

The birthday party itself went well. Visitors were entertained with demonstrations of various technologies in the lab itself, and some were able to ride in one of the SMLL’s automated cars. Networking was undertaken. Food and drink were consumed.

Additionally, speakers entertained. Paul Campion, TRL’s CEO, was master of ceremonies. He spoke about the origins of the SMLL as being in the partnership between Government and Business, something that Great Britain does well. This theme was continued by Michael Talbot from CCAV, and Karla Jakeman from Innovate UK. Both these speakers touched on the importance of innovation in taming the complexity of future mobility, relying as it will on customer demand, infrastructure, new technologies, business models and energy vectors, and the management of all the assets (including active travel assets). Michael Hurwitz from Arrival caught the attention with his “…elevating the experience” definition of smart mobility and discussed some disruptive approaches to ensuring that the really big gains in carbon reduction are targeted first, and that innovation is directly prioritised, even if it means a deliberate inclusion of ‘non-transport people’ in bringing the new ideas.

The main theme detectable in the presentations was that conversation was always focused on the future. Importantly though, this future includes the challenges we face in mobility – decarbonisation, safety, accessibility, sustainable development – as well as the technologies and enablers like electrification, digitisation, and of course automation and artificial intelligence.

Survival of the species

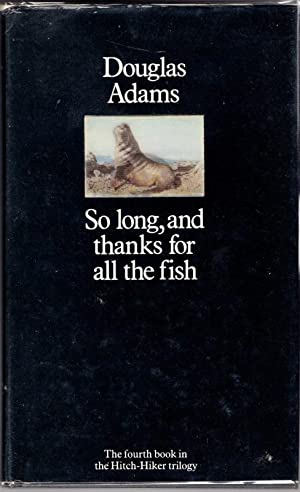

At the end of the day, we were treated to a short and excellent presentation on the latter of these topics by Robbie Stamp, who is a leading thinker on the topic of AI. (He has slightly more complex interests than just AI – see here The title of the presentation (‘Sentient Puddles and the Governance of AI’) referenced a central idea that motivated Douglas Adams (when writing the ‘Hitchhiker’s Guide…’ novels) with whom Robbie had worked in the pioneering years of another enabling technology (the internet). That idea is that if we just assume that we have some ‘right’ to survive as a species, we forget the need to design systems and solutions to help us achieve this. Such is the situation in which we find ourselves now, with emergencies related to climate, air quality and obesity that mobility solutions can contribute so much to helping address – if we get them right.

The presentation covered a number of knotty thought experiments around AI, and its role in all areas of human life – ‘self-driving cars’ being only one. The take-home message was that AI needs to be designed with great care, and in doing the designing we need to ask a much more holistic set of questions of the use of AI, beyond simply whether it performs ‘better’ or ‘as well as’ humans performing the same tasks. For example, AI may be better than humans at spotting patterns or predicting risk, which may lead us to decide that we want such systems involved in mobility, or healthcare, or any other area; we also need to ask, however, what we are willing to allow the AI to do with this advantage, and where the lines are than only humans can cross.

These ideas made me think about the need for us to remember the user in ‘smart mobility’ – such is my default way of thinking, as a psychologist. The technology may be really exciting but unless we make smart mobility work well for all of us (including the planet and environment in which we live, as a species) nothing ‘smart’ is really going on. Let’s take the opportunity to do smart mobility with people, not merely to them.

After the buffet and conversation, I bumped into Robbie outside as I was unfolding my bike for the return to Waterloo (a slightly more direct 60-minute ride). We chatted briefly, and I reminded him of the fact that in ‘So long and thanks for all the fish’ – the third book in the ‘Hitchhikers Guide’ series – TRL is mentioned in the text (in an anecdote about a leather jacket having a car crashed into it to give it a ‘battered look’). Another piece of TRL history.

Epilogue

TRL is 88 years old. It has spent a great deal of its life making vehicles safe, and roads safe, and people safe. The Smart Mobility Living Lab is a year old. As it grows, with its Innovation Community watching over it, it is taking its first steps towards making whole mobility systems safe, liveable, accessible, and sustainable. And, of course, smart.