Tufty is 69; he was created in 1953 to lead a RoSPA campaign on child safety and famously specialised in helping children cross the road safely. Not bad for a red squirrel (usual life expectancy 10 years unless you try and live in England in which case you’re extinct.) (I must admit my favourite TRL report is the “Tufty Club enquiry” of 1973 which concluded, amongst other things, that “animal characters should be used to illustrate road safety” but that the Tufty books “could be improved by attention to the style of writing and the standard of illustrations.”). For those of us of, ahem, a certain age, Tufty may summon up comforting memories of road crossing drill. Younger people (but, perhaps, still not particularly young) may remember the Green Cross Man who took over Tufty’s job in a TV-friendly superhero style. Is it too cynical to suggest that if you are younger than that, then road safety training was replaced by the perceived need for your parents to invest in an SUV to take you to school instead? Perhaps the fact that the actor who played the Green Cross man went on to play Darth Vader is not, after all, just the answer to an amusing showbiz trivia question…

But what prompts this poundshop social history? Well I was musing, over the course of Road Safety Week, about the different approaches we have taken to improving safety over the years. Over the long run new types of transport tend to start dangerously and, as we work out what works and what doesn’t, they get safer and safer. The railways, for instance, used to kill people at a shockingly high rate until we learnt to separate people and trains, and separate trains from each other. (If you are interested in this (and much else about trains and the people who use and run them) then I cannot recommend Simon Bradley’s “The Railways” highly enough). When automobiles were first introduced they, too, were dangerous to drivers, passengers and, well, everyone else, in equal measure. But we have engineered safety into cars and roads and educated people directly, and by counter-example, so that the culture of road users in and out of cars helps to keep everyone safer.

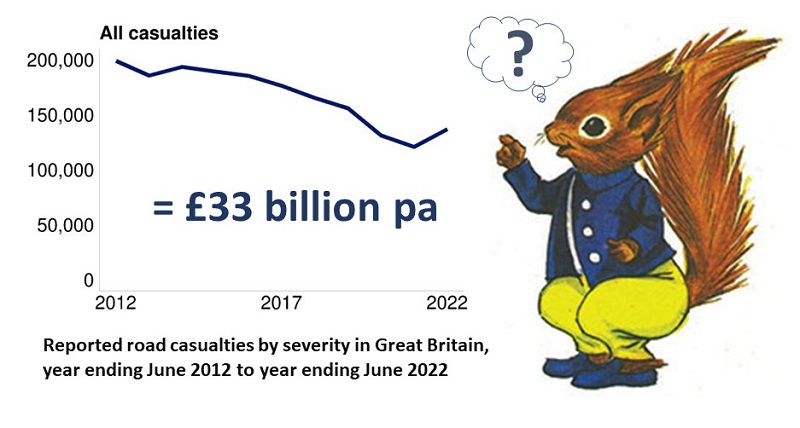

And road casualties have come down even as miles travelled have gone up…until recently, when the trend has flattened out. As a society, here in the UK there does not seem to be much urgency about between 1500 and 2000 deaths a year on the roads, and as a proportion of the population, it is a small number. For every person killed there are 16 or 17 who have a ‘serious’ injury…many of which are life-changing…and this is every year, remember. There are probably few people reading this who have not been involved, or have a family member or close friend involved, in a road traffic collision with unpleasant consequences. (On top of this for every fatality another 66 people have ‘slight’ injuries…but we, collectively clearly think that’s a price worth paying.) Recently an opinion in the British Medical Journal, no less, highlighted road safety as a critical public health issue that is not correctly prioritised. Even using the word “accident” can lead us to think these things just happen, but in reality, research shows us they are preventable.

Humans are notoriously bad at objectively judging risks (the perceived seriousness of (vanishingly rare) air or rail crashes seems to be much higher than that of the objectively much more likely risk of dying on the roads)….but still it seems odd that we seem to be so relaxed about this. Even if we take a cold-hearted and economically reductive perspective on this, the weighted economic cost of road collisions in the UK is over £33 billion every year: strange at this time of recession, energy cost crisis and general belt-tightening that we are content as a society to waste the equivalent cost of the UK’s primary and pre-primary education budget, in perpetuity, on this of all things. I wonder what the Tufty Club budget was?

Perhaps the problem is that we cannot see how it could be better. Perhaps squeezing out the last injuries and incidents is just too hard: we’ve taken all the low-hanging fruit, made all the obvious improvements and this is as good as it can get?

Tufty and the Green Cross Man were all about personal responsibility for avoiding road traffic incidents and of course this is important, but the main drivers for reductions in collisions and harm caused have been engineered improvements in vehicles, infrastructure and systems. Safety is an emergent property of systems and so, frustratingly, there is not (cannot be) a simple answer to what is a complex and complicated problem. Making our roads still safer and getting to Vision Zero will require changing lots of things. This does not mean it is impossible; famously Oslo achieved an entire year with no pedestrian or cyclist fatalities (and that was by design, not by, err, accident.)

So here’s an idea. Let’s create a place where we collect all the best practice, no matter where it occurs. Let’s build a model for how to make our roads safer still, and how we get to Vision Zero. Where we don’t have the answers let’s identify the problem and do the work to find the solutions. Let’s task them with providing a toolkit of designs, process, systems, education…whatever it takes. It can become the place where local and central government can go to get proven ways of making our roads safer. Yes, it’ll cost some money…but if we can save the economy billions of pounds a year it will justify itself fairly easily.

Do old red squirrels go grey, I wonder. No matter: I can see Tufty nodding his head at the ambition to complete the job he started…