A week of decarbonisation

Between the 31st of October and the 12th of November 2021, at the COP26 summit in Glasgow, the world’s governments met and formulated a plan to avoid temperature increases in the Earth’s climate at levels that would be catastrophic to the survival of humanity. Reactions to the deal agreed at the summit could be summed up in the phrase “a start, but not enough.”

In the middle of the week of COP26, the Highways UK conference took place at the NEC in Birmingham. Transport is responsible for over a quarter of the UK’s CO2 emissions, and road transport is responsible for around 90% of this share. Given these facts, and the coincidence with COP26, it is hardly surprising that decarbonisation dominated the agenda.

99 Miles to Highways UK

In the weeks leading up to the Highways UK conference, I became aware of an ironic situation regarding my own attendance. The facts were thus:

1. I was due to attend to deliver a seven-minute presentation on how decarbonising transport and solving some of the other crises we have (air quality, health) requires a commitment to travel less by car, and more by active modes such as cycling and e-cycling.

2. The NEC was 99 miles from my house, and despite the lessons learned in the last 18 months on how effective hybrid working can be, there was no option to dial in.

The clear answer to this was for me to take the train, but there were a couple of things against this option. First, I really don’t enjoy train travel – it makes me feel ill and I generally end up very tired after a journey of more than an hour. Second, ‘taking the train’ did not seem to me to be ambitious enough in terms of embracing the very substantial behaviour change that we think is going to be needed if we are to reduce our climate impact. My next thought was then simply ‘oh – I’ll cycle’. However, I am not a ‘99 miles’ kind of cyclist, something that I feel I need to change, given the lengths some other people were going to. A compromise was needed and found. I would catch a train from Wokingham to Banbury (two relatively short trips with a change at Reading) and would then spend a long lunch break (2 hours approx) cycling around 22 miles to Stratford-Upon-Avon the day before my talk. An overnight stay would set up a similar distance cycle early the next morning, to reach the NEC by mid-morning, allowing for a breakfast stop on the way. Readers of my last blog will be delighted to know that all of this was to be done on a Brompton that is too small for me; I really need to commit and get my own, rather than borrowing Kim's

So, on Wednesday the 3rd of November, off I set. My usual cycle to Wokingham station, a train to Reading and then on to Banbury with the bike folded all went without a hitch. At Banbury, I switched on a well-known mapping app, mounted my phone to the handlebars, and set about the cycle to Stratford.

Part of the point of doing the trip in this way was to understand how plausible a 20-odd mile cycle was as a genuine option for ‘normal non-Lycra-wearing cyclists’ like me wanting to take it on as a commute. Specifically, I wondered, what was the infrastructure like? The answer is ‘patchy’. Essentially the route I took on day 1 after leaving Banbury town was a main road punctuated by occasional pathways, and the one constant source of irritation was not (as I had feared) the motor traffic, but the vibration from the extremely poor surface. The 16-inch wheels on the Brompton were certainly not helping of course; in this respect I felt more empathy than I ever had before for drivers of cars with sporty suspension and low- profile alloys.

I didn’t feel much empathy for the motor traffic when it was an issue. While it was not a constant source of concern like the pavement surface, when it became an issue it really grabbed my attention. I think the closest pass I experienced at anything more than very slow town speeds was around a tenth of the one and half metres recommended in the Highway Code. A public service announcement for motor vehicle drivers thinking about passing a cyclist closer than what is recommended at speed – this is NEVER justified.

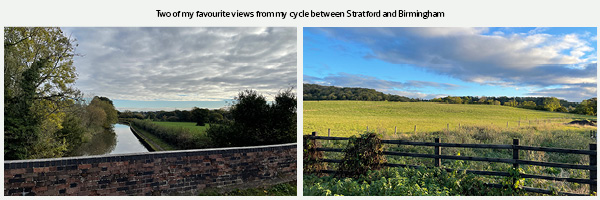

Some 'transport infrastructure'

There are undoubtedly barriers to cycling other than the infrastructure and traffic. One thing I had been lucky with for example was the weather. I knew it was looking dry and not too hot – an ideal combination to avoid arriving a sweaty mess at my destination. Had the weather been inclement, I may be making this point less strongly, but I can honestly say my current position on this agrees with this recent article in the Journal of Transport Geography; the whole thing would have been much, much more enjoyable, and would have come across as a much more practical everyday solution, had there just been space in which I could do my thing on a good smooth surface, while safe in the knowledge that people travelling in cars could do theirs. What is currently on offer (see example above) is not quite there yet, even when it constitutes specific areas for cyclists (or even footpaths).

The trip from Stratford to the NEC the next day (another 21 miles) was pretty much a copy of day 1, although there were far more options to get off the roadway and onto (some) cycle tracks and footpaths. On the topic of cyclists on footpaths, which I know may come across as contentious to many people, I will say this. I took every opportunity to ride on them and saw only one pedestrian on the whole trip on stretches when I was on the footpath (never in towns – just on the main roads). That person was on the other side of the road too, so I didn’t need to exercise my usual reaction on the byways on my office commute, which is always to slow down or stop, to give way. A casual glance at the pictures of the various options I had on day 2 will also confirm that using space meant for walking is not the preserve of just cyclists. I bet the owner of that car doesn’t even pay footpath tax.

I arrived at the NEC slightly later than planned but in good time for the talk. Change into shirt, check bag and bike into cloak room (the helmet was extra – bizarrely), some minor ‘networking’, a quick glance at the lovely TRL stand, and I was up on the ‘Big Ideas’ stage, alongside my boss, Richard Cuerden. No pressure, then.

Seven minutes at Highways UK

In my seven minutes of airtime, I gave the first half of a presentation designed to provoke some thoughts around what the whole road network is for, in an age where we face three crises of such urgency that we really cannot afford to be relying on half-measures. First, the climate emergency dictates that we need to reduce carbon emissions by 50% within the next eight years. Second, we have an air quality crisis, with estimates of tens of thousands of deaths a year in the UK, and road transport being a major contributor. Third, we have an obesity epidemic, with one in five 10-11 year-olds in England obese, and a further 14% overweight.

Active travel helps with all of these. Reactions to the COP26 deal have been quick to point out that it has been far too much about electric cars, and far too little about active travel. Local initiatives abound on this topic, but it strikes me as odd that no-one is thinking much about this in relation to roads outside urban areas – even the strategic road network. For example, in the UK Net Zero Strategy there is a £2billion investment in cycling and walking, but this is focused on towns and cities. In the Road Investment Strategy 2 document there is mention of some cycling investment alongside parts of the network, but very little detail on levels. When the budget for RSI2 is around £652,000 an hour, one could be forgiven for thinking that savings could be found in some road schemes to prioritise opening the network, and the many miles of local ‘fast’ A-roads and B-roads to active modes where at all possible.

I am aware that this is a rather odd idea on first hearing, but in a week when I have read a convincing argument for lowering the voting age to six, I feel like I should persist. My basic contention is this; we need active travel to be a major part of the future of mobility, and if it is to have a serious impact on car use, I suspect it needs to be an option for the kinds of journeys I describe above.

Luckily, there are two reasons to think that it could work. The first is electric bikes, which based on personal experience testing one after the trip (how I wish I had it on the trip), and based on evidence, open up much longer journeys for cycling when the infrastructure is available. “Twenty miles though Shaun? Might that be a bit long?” I don’t know – but I will stick with it for one main reason – it is a stretch objective in a time when we all need to change our behaviour to a greater extent than we may be comfortable with. The second reason to be optimistic – and bear with me on this – is Smart Motorways. Despite the recent headlines they have been suffering, I suggest they are a great example of how ‘innovation’ and ‘outside the box thinking’ can be successful at solving difficult issues on the strategic road network. The fact that in the case of Smart Motorways the problem at hand (greatly increased traffic growth) should have been managed entirely differently – like by reducing demand – is not the point. Smart Motorways are proof that National Highways can think differently, when needed. They can lead the thinking on this and bring other road authorities with them.

Where, then, are the ‘Shared Motorways’? Where is the progressive thinking about taking strategic road network space away from motor traffic, and making it available for those on bikes and e-bikes? I’m not advocating cycle lanes on the M25, but I would have thought that with some innovation and a fresh perspective, we could have a crack at making active travel be something people do on fast A and B roads, not just around them on the odd bits of infrastructure that does exist (more of this too though, please). Cycling between towns, not just in them, should be easy and safe for those who want it.

Some readers will believe this all a bit silly. But as I said on the day of my presentation, I’m not here to provide the ‘how’; just the ‘what’ and the ‘why’. It was the Big Ideas stage, not the Well-thought-through Feasible Solutions stage. I just believe that active travel, and especially e-biking to replace medium distance car journeys, needs to be a very large part of the future of transport. Now – will someone please just tell me how to make it happen?