When politicians say ‘war on the motorist’ they probably think they are just using a phrase that at best has entered common usage, or at worst has been shown in focus groups to do the best job of appealing to polarised viewpoints. I doubt that many who use the phrase stop to really think about its connotations. I would argue that there are two ways in which this phrase is deeply misguided, and perhaps even offensive.

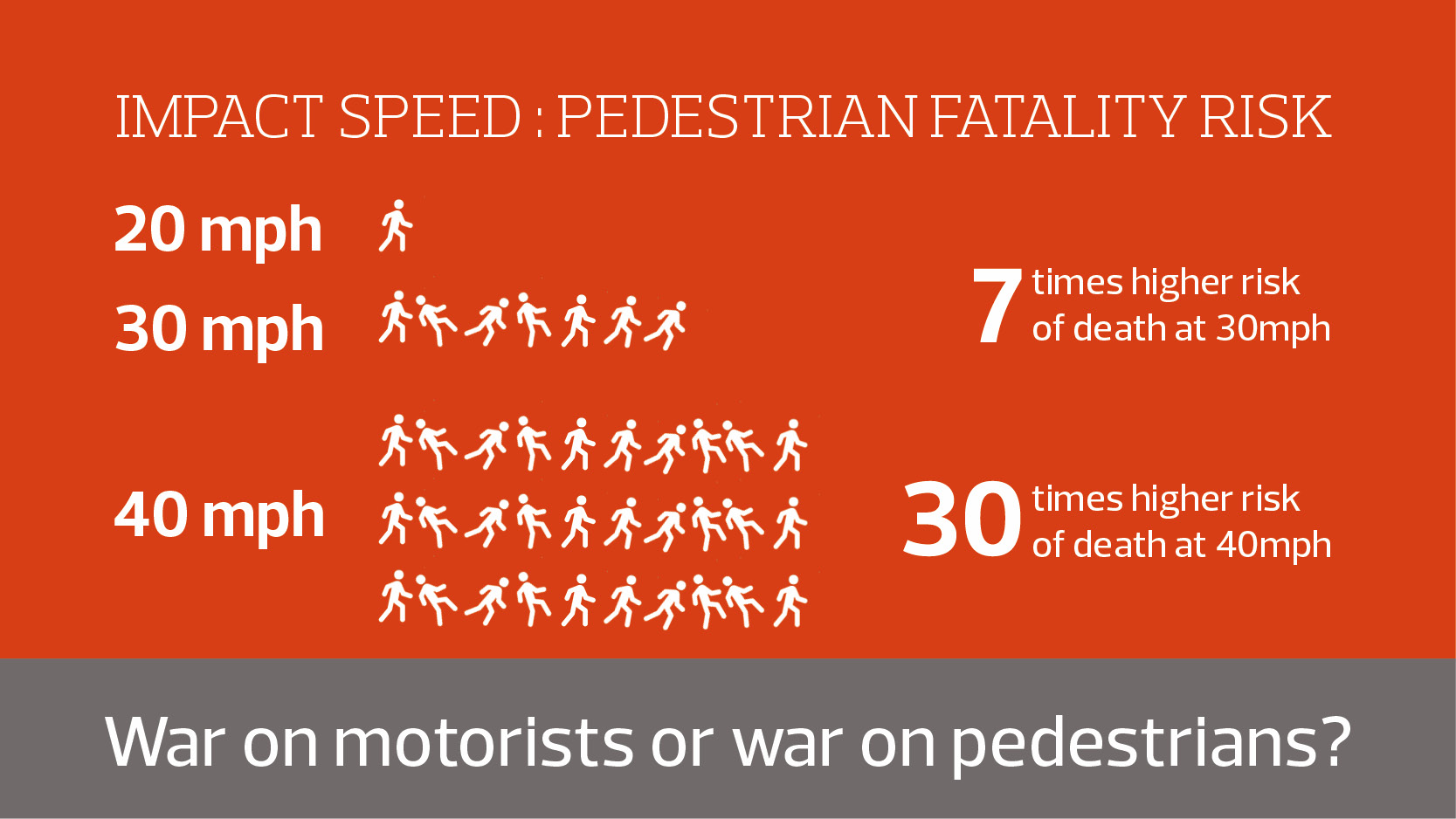

First, it uses a word - war - that is synonymous with violence, but then points this meaning at the car drivers who are relatively safe from harm in lower speed collisions, rather than the pedestrians and other vulnerable road users who are more likely to suffer violent injuries. The added irony is that the injuries sustained by those vulnerable road users in collisions with vehicles, like those sustained by combatants in wars, are often substantial (even at 30mph). If politicians wish to retain some credibility in their language, rather than talking about a 20mph speed limit being a (figurative) 'war on the motorist' they would do well to talk about a 30mph limit being a (literal) 'war on the pedestrian' in terms of the injuries sustained.

Second, if we look at data on deaths in service for the UK armed forces - the people who actually fight in wars - we can see that historically 'land traffic accident' is one of the top causes, even in years when there was active conflict such as the war in Afghanistan. Against such a backdrop, the use of the word 'war' in describing the trifling inconveniences experienced by car drivers driving at 20mph again seems rather inappropriate; road traffic collisions are a great source of danger for the very people we employ in real wars to protect our country's interests.

By advocating for higher speed limits, politicians are advocating for more collisions, and more severe injury outcomes. By using the phrase 'war on the motorist' they not only offend, but they draw attention away from the substantial injury burden imparted by road traffic collisions. A frank admission of this would be more useful to the wider debate here than platitudes designed for headline writers.

The real debate of course is larger than language. It is addressing the question of why we do not treat violence and injury from road traffic in the same way we treat violence and injury from other sources - using a true systems-based approach with known evidence-based interventions. Others have written on this broad challenge. In 2002 for example a whole issue of the British Medical Journal was devoted to it (editorial here). This paper from 2013 discusses the topic with a focus on societal acceptance of road traffic injury as an inevitable consequence of cars, and how this is a necessary narrative for cars to stay dominant in the transport mix. To be fair, in 2023 we find ourselves in better shape, with for example pedestrian protection being a core part of vehicle safety. Nonetheless in a world in which road traffic collisions are killing around 5-6 times more people a year than asbestos-related diseases, a field in which it took decades for clear evidential links to be acted upon, there is clearly still much to be done.

And even if the debate is larger than language, language is still important in the debate. A society in which we see injury and death on the road for what it really is - avoidable violence - will hopefully be a society in which we are slower to resort to lazy metaphors in defending our resistance to change. And for those of us who walk and cycle around motorised traffic all the time, hopefully it will be a world in which that traffic is just slower in the literal sense.